Amanda de Oliveira Silva, Small Grains Extension Specialist

In recent years, we have received numerous questions about the potential yield losses associated with planting wheat later in the fall. Farmers often ask if variety selection or management practices, like adjusting seeding rates, should change when planting is delayed.

As weather patterns become more unpredictable, with fall droughts and floods causing planting delays, this topic has become even more critical. Additionally, the late harvest of summer crops like soybeans and cotton in double-cropping systems further pushes wheat planting into late fall. The rise of herbicide-resistant weeds has also led farmers to delay planting as they work to control late-fall emerging weeds culturally.

Recognizing these challenges, our program has focused on studying wheat performance under late planting conditions. We aim to:

- Estimate potential yield penalties and understand the factors contributing to them when planting is delayed from October to December in north central Oklahoma.

- Evaluate variety performance under late planting, particularly focusing on varieties with different maturity ranges.

- Determine the need to adjust seeding rates as planting is delayed.

From 2021 to 2023, we conducted a study in Stillwater and Lahoma to evaluate how delaying planting dates from October to December would affect wheat performance (Figure 1). We tested two seeding rates, and nine winter wheat varieties adapted to Oklahoma, including a short-season variety covering a range of maturity classes (Table 1). The standard seeding rate of 870,000 seeds per acre reflects the average rate used in Oklahoma, equivalent to about 60 lbs/acre for wheat with an average seed size of 14,500 seeds per pound. To compensate for the approximately 40-day delay in planting between the October and December treatments, we increased the seeding rate by about 60%.

Table 1. Information of historical maturity patterns of all varieties tested in this study at early-fall planting date.

Based on the data from this study, surprisingly, late-fall planting yields (79 bu/ac) exceeded early-fall planting yields (54 bu/ac) in four of six site-years, or by 5 bu/ac averaged across all site-years (Figure 2).

Does delayed planting affect wheat development?

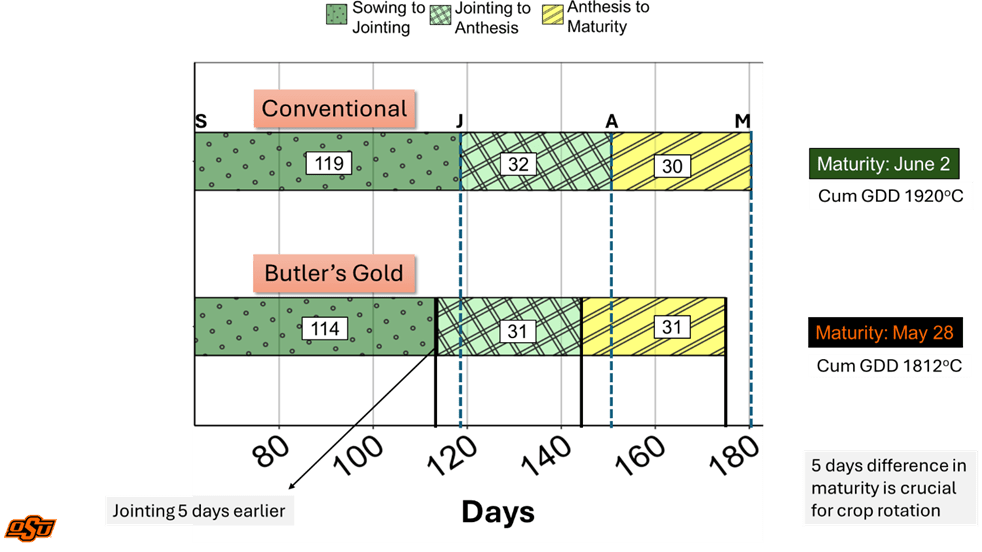

In our trials, late-fall planting was delayed by 41 days compared to early-fall planting. Wheat varieties planted later reached heading and maturity five days later than when planted earlier.

Late-fall planting reduced the period from planting to jointing by 28 days. The critical period from jointing to heading, which is vital for yield formation, was shortened by only seven days. The grain-filling period was shortened by only two days compared to early planting. Interestingly, varieties that reached jointing, heading, and maturity early at early-fall planting did so when planted late. For example, the variety Butler’s Gold reached jointing, heading, and maturity earlier than the other varieties in late-fall planting. Baker’s Ann followed closely, reaching these stages within the same day or up to three days later, while Bob Dole reached jointing and heading five days later and maturity six days later than Butler’s Gold.

Do wheat varieties perform similarly when planted late in the fall?

In our trials across multiple sites and seeding rates, Bob Dole was the top-yielding variety, producing 73 bu/ac in late-fall planting. However, its yield was not statistically higher than most other varieties tested, except for Butler’s Gold, which yielded 62 bu/ac (Figure 4). Varieties that performed well tended to accumulate more biomass by harvest and produced more grains per unit area (Figure 5).

A key observation was the trade-off between biomass production and maturity. Early maturing varieties like Butler’s Gold and Baker’s Ann had the lowest biomass production when planted late. This suggests that developing early maturing varieties with the ability to accumulate more biomass could improve their adaptability to late planting conditions. Further, the short-season variety Butler’s Gold had greater grain weight and above average grain protein concentration than the other varieties tested (Figure 5).

Does seeding rate need to be adjusted for delayed wheat planting?

Our trials showed that increasing seeding rate did not result in a yield increase at late-fall planting across all varieties and site-years (Figure 6). Although the seeding rate affected some yield components, it did not translate into higher yields. The higher seeding rate increased the number of wheat heads per unit area but reduced the number of grains per head compared to the recommended seeding rate (data not shown). As a result, the total grain number per unit area — and ultimately the yield — remained the same for both seeding rates. Thus, our results suggest that increasing the seeding rate in late planting may not provide a yield advantage.

Take home

• Late planted wheat in Oklahoma showed no consistent yield loss compared to early-fall planting

• While the designated short-season variety, Butler’s Gold, did not outperform the other varieties at late sowing, its true value in a late-planted management system is derived from its one-week earlier harvest maturity. It also showed good end-use quality characteristics with heavier grain and above-average grain protein concentration than the other varieties .

• Varieties with better biomass production and grain number performed better with late sowing.

• Though this may defy logic, farmers do not need to increase seeding rate when facing the need to sow late, based on our results thus far.

Contributors:

Israel Molina Cyrineu, PhD student

Brett Carver, OSU Wheat Breeder

Tyler Lynch, Senior Agriculturalist for the Small Grains Extension Program

This research has been partially supported by OSU Wheat Research Foundation and Oklahoma Wheat Commission

What were the weather conditions for each year? Ambient temperature, soil temperature, soil moisture at planting, after planting, etc?

Hi Mark,

2022 and 2023 were pretty dry, but freeze events seemed to affect the wheat planted in October. We saw more late-spring freezes in the October-planted wheat than in the December planting.

Let me know if you’d like to see the complete weather data. I would be happy to send it via email!

Thanks for your comment, and sorry for the delay in getting back to you.

Amanda