Amanda de Oliveira Silva, Small Grains Extension Specialist and Ashleigh Faris, Cropping Systems Extension Entomologist

Wheat planting in Oklahoma is off to a slow start due to extremely dry conditions, with only 32% of wheat planted as of October 7 (according to the USDA Crop Progress Report).

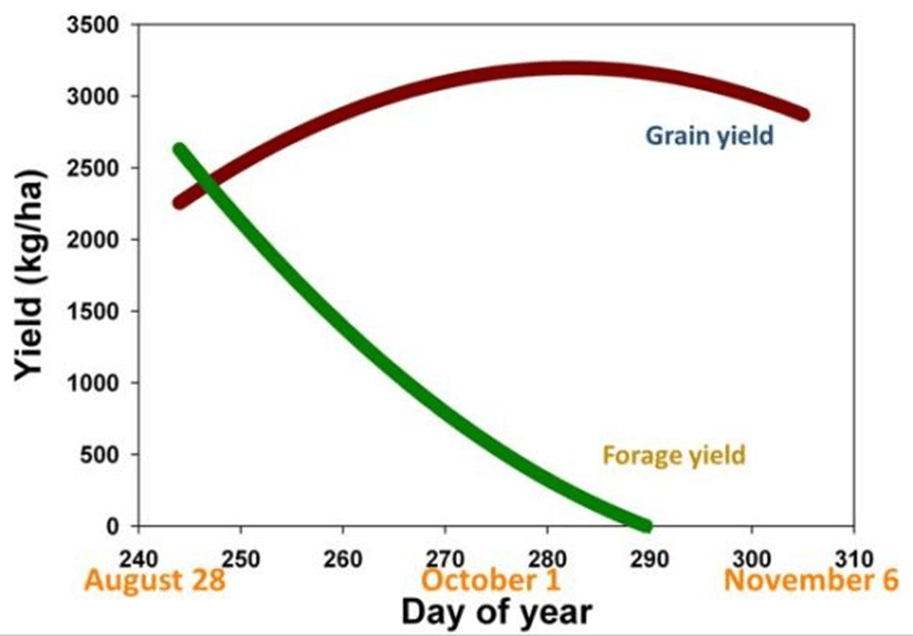

For most of Oklahoma, the optimal time to plant dual-purpose wheat is between September 10-20 (approximately day 260 in Figure 1). This period represents a balance between achieving good forage production and minimizing the risk of grain yield loss. Planting earlier can provide more fall forage potential but is usually only recommended if wheat is intended for grazing or “grazeout.” If you are planting wheat just for grain, you could wait at least 2-3 weeks after the dual-purpose planting window, which puts the best time for planting around mid-October (approximately day 285 in Figure 1) in many parts of the state. We have been evaluating how delayed wheat planting affects wheat yields, and it appears there might be more flexibility in the planting window than previously thought. I will be sharing more details about this research in an upcoming post!

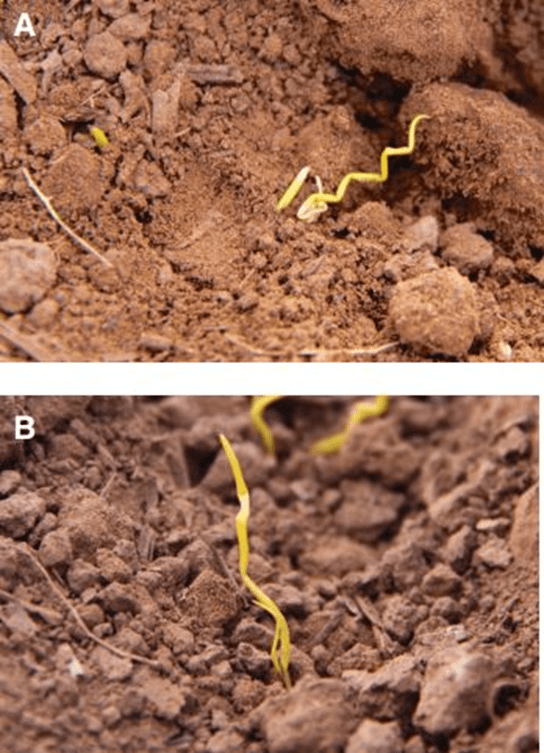

Rainfall on September 22 helped some fields in north-central, northwest, and Panhandle areas, and wheat that was planted before then has now emerged and looks good, though more rain would certainly help (Figure 2). In the fields we planted in Panhandle and northwest, we found moisture at about 1.5 inches deep, but the drought is holding us back in other parts of the state.

For fields where wheat was planted before the September rain, we are receiving reports of fall armyworms. They have been especially active in north-central Oklahoma over the past week. We recommend checking your fields daily after wheat emerges. The worms are small and hard to spot, but you may notice symptoms like “window pane” feeding on the leaves (Figure 3). Also, check under crop residue where they might be hiding from the heat (Figure 4).

Below is some information regarding monitoring and management of fall armyworms. Typically, fall armyworm population spikes are due to increases in precipitation in summer months. Fall armyworms are identifiable due to the light colored, inverted “Y” on their head (Figure 5). They are generally light tan to light green caterpillars that have a brownish-black head (may appear orangish). For more on the biology of the insect and its identification, check out the EPP-23-21 e-Pest Alert from this past summer.

Fall armyworm larvae will begin to consume vegetation in the early instars (1-3) but often this damage goes unnoticed because of the small amount consumed. As fall armyworms enter the later instars (4-6) the rate of consumption increases, and damage is more noticeable. The reason for rapid crop loss at this stage is caterpillars do most of their feeding (80-90%) in the final two instars. Fall armyworms cause damage by defoliating leaves and cutting seedlings at the surface level. Small larvae, unable to completely chew through the leaf, will often feed on vegetation by scraping it, lending to a windowpane appearance (as mentioned above, Figure 3).

Recommendations

Begin scouting for fall armyworms as soon as wheat emerges, particularly in the morning hours at the edges of wheat fields that share borders with pasture or road ditches. Look closely for signs of windowpaned leaves and the fall armyworms themselves. Treat if three to four larvae are found per foot of row AND feeding damage is evident. The early instars are more susceptible to insecticides so early detection is important for providing effective chemical control. While pyrethroid-based insecticides are low-cost, they are often ineffective when populations of fall armyworms are high. Instead, consider mixing a pyrethroid with another product that has chlorantraniliprole or diflubenzuron as an active ingredient which have a longer residual. Chlorantraniliprole products offer the advantage of being rainfast as well as protection against bigger fall armyworms. Products with diflubenzuron have a long residual but do not work well on larger worms. The good news is first frost will help knockback fall armyworm populations, until then producers are encouraged to have fall armyworm scouting as part of their daily routine and to be on the ready to spray when threshold is met.

We will not get relief from fall armyworms until we get a killing frost, so keep vigilant!

Reach out to us and contact your county Extension office for more information.

Amanda Silva – silvaa@okstate.edu

Ashleigh Faris – ashleigh.faris@okstate.edu