Amanda de Oliveira Silva, Small Grains Extension Specialist

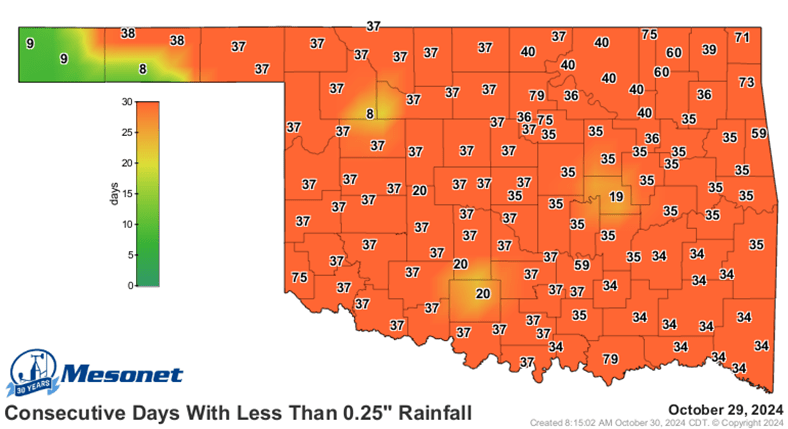

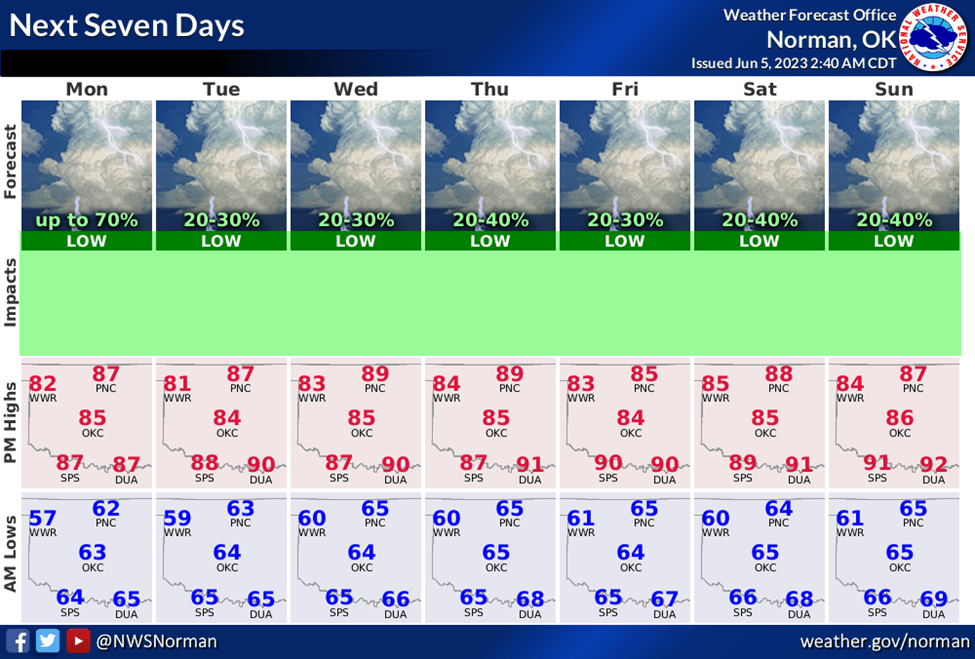

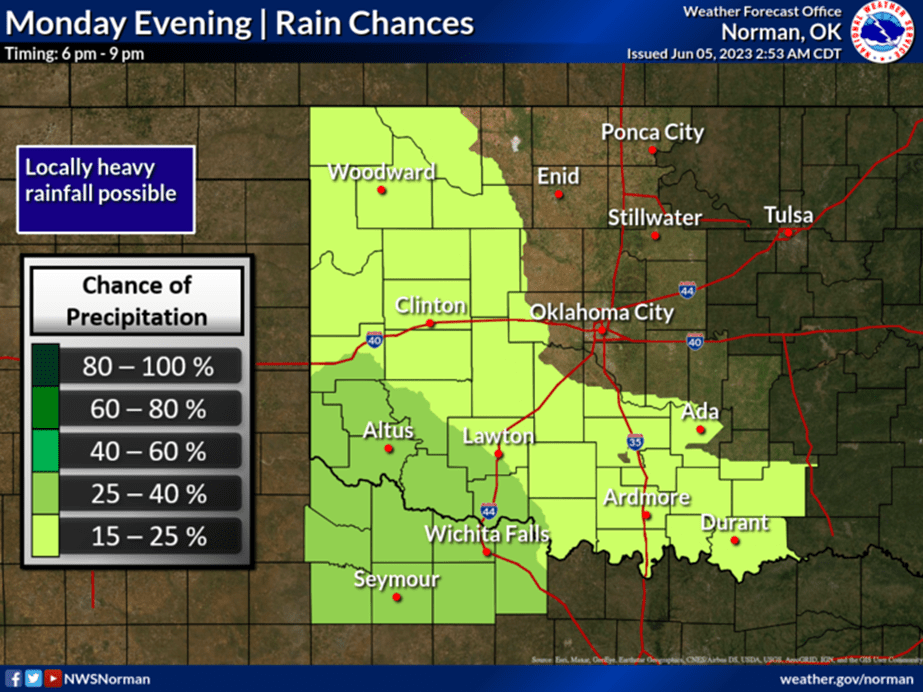

Oklahoma’s wheat planting season was heavily impacted by severe drought. The season was essentially divided into two main rain events that impacted crop growth. Dual-purpose producers who planted before September 22 established good stands in early fall. Warm temperatures promoted rapid growth, but the crop began to decline as drought conditions intensified (Figure 1).

The next significant rain event occurred about a month later, almost past the optimal wheat planting window in some areas. With rain in the forecast for late October, many farmers chose to “dust in” their wheat ahead of the rain, while others opted to wait.

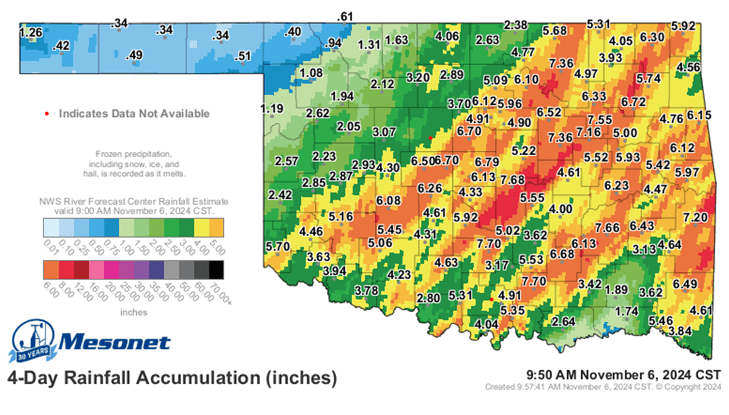

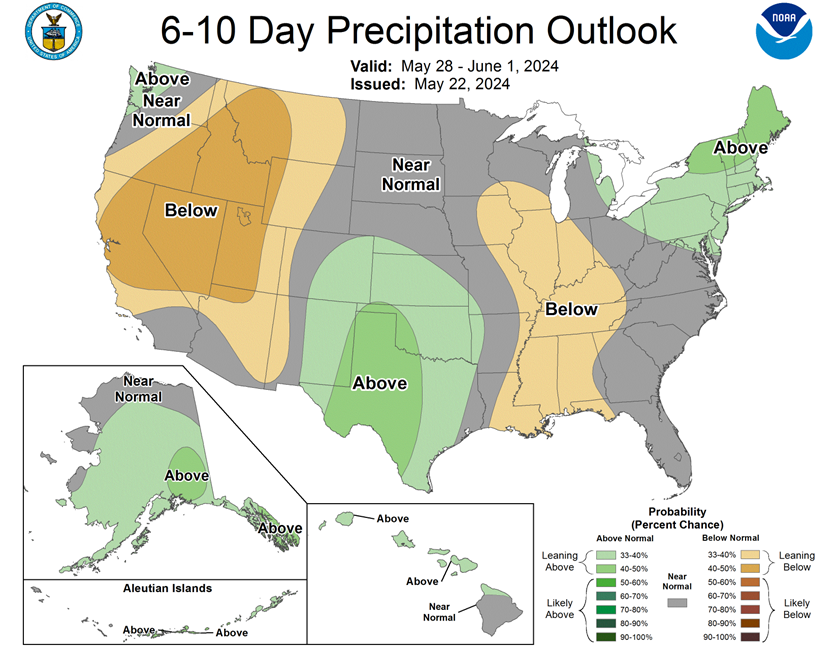

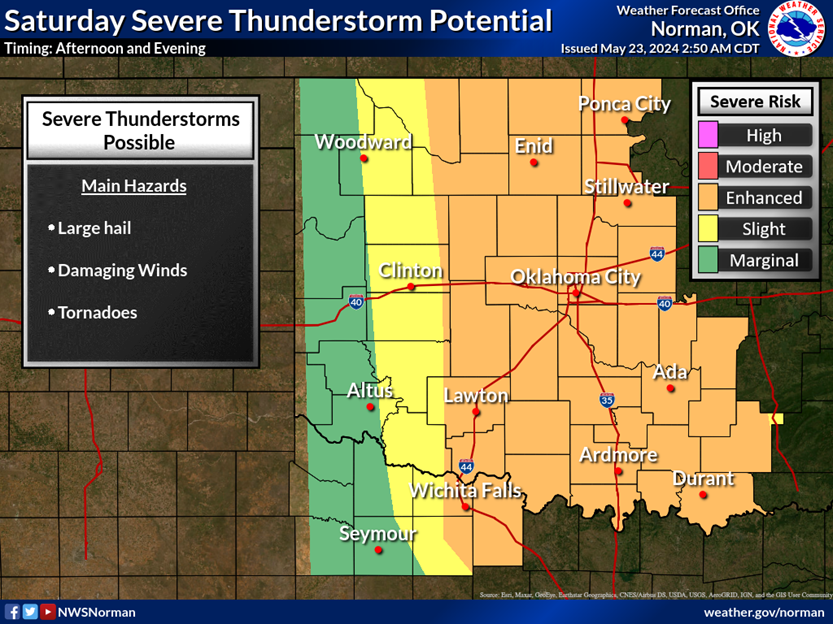

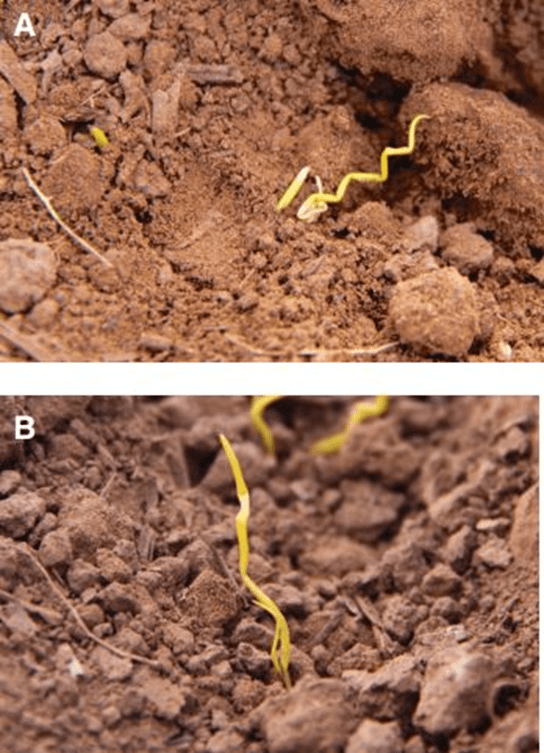

In early November, wheat-growing regions across Oklahoma received between 1 and nearly 8 inches of rain, while the Panhandle saw up to 20 inches of snow from November 5–9 (Figure 2). These events quickly shifted conditions from extreme drought to flooding. Although November temperatures were above average (~53°F), seeds remained in cool, wet soils for weeks, leading to slow or failed germination. Some areas experienced standing water and soil crusting, causing plant losses. As a result, wheat stands across the state vary widely, with some fields establishing well while others remain highly uneven, contributing to overall low fall forage production.

For grain-only wheat sown in late fall, stands are just now closing in some areas. Though still small, the crop appears to be growing well.

Yield loss for grazing past first hollow

For the producers with available pasture for spring grazing, preserving some leaf tissue after grazing will be important for future grain crop. Ideally, at least 60% canopy coverage (as measured by the Canopeo app) should remain to support crop recovery after grazing (PSS-2170). Extending grazing for an additional two week past first hollow stem (FHS)—particularly under conditions unfavorable for plant regrowth and canopy recovery—could reduce wheat yield by approximately 60% of its potential (Figure 3).

The first hollow stem stage as an indicator for cattle removal from wheat pasture

The first hollow stem stage indicates the beginning of stem elongation or just before the jointing stage. It is a good indicator of when producers should remove cattle from wheat pasture. This occurs when there is 1.5 cm (5/8”, or the diameter of a dime) of hollow stem below the developing grain head (Figure 4). This is the optimal period because it gives enough time for the crop to recover from grazing and rebuild the canopy. Also, the added cattle weight gains associated with grazing past the FHS are not enough to offset the value of the potential reduced grain yield (1-5% every day past FHS) (Figure 3). The wheat variety, severity of grazing, time when cattle are removed, and weather conditions after cattle removal determine how much grain yield potential might be reduced.

Methods for scouting for FHS

- Check for FHS in a non-grazed area of the same variety and planting date. Variety can affect FHS date by as much as three weeks, and planting date can affect it even more.

- Dig or pull up a few plants, split the largest tiller longitudinally (lengthways), and measure the amount of hollow stem present below the developing grain head. Plant tissue must be removed below the soil surface, because the developing grain head may still be below the soil surface.

- If there is 1.5 cm (~5/8″) of hollow stem present, it is time to remove cattle. 1.5 cm is about the same as the diameter of a dime (see picture below).

- Find detailed information on FHS and grazing by clicking here.

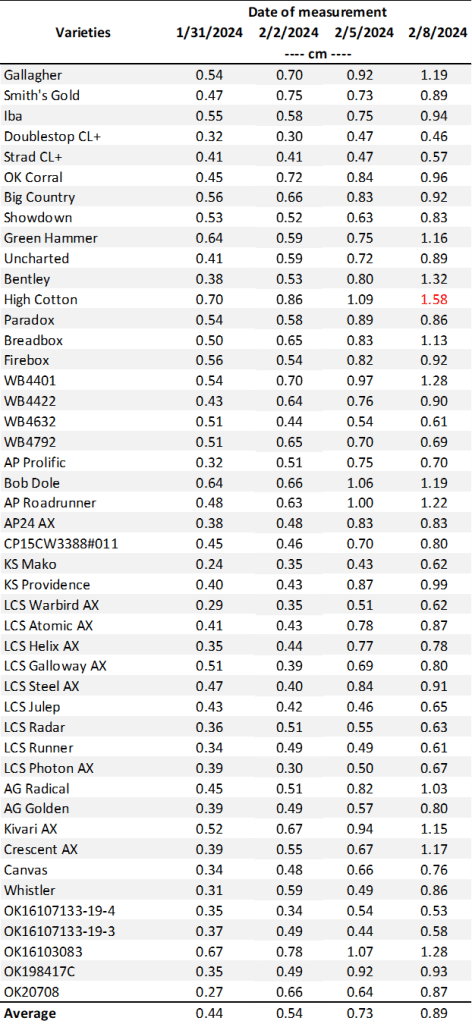

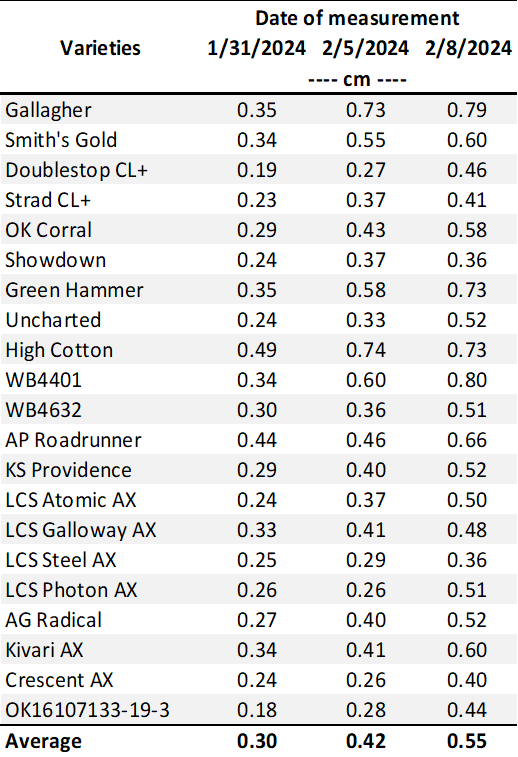

OSU Small Grains Program monitors FHS occurrence on a twice-per-week basis

As in previous years, we will continue monitoring FHS occurrence in our wheat plots at Stillwater and Chickasha and share updates on this blog. In past years, our forage trials—where FHS samples are collected—were seeded early to simulate a grazed system, though forage was not removed. This method created an accelerated growth environment, allowing us to identify the earliest onset of FHS. Varieties that reach FHS earliest in these trials should be closely monitored in commercial fields.

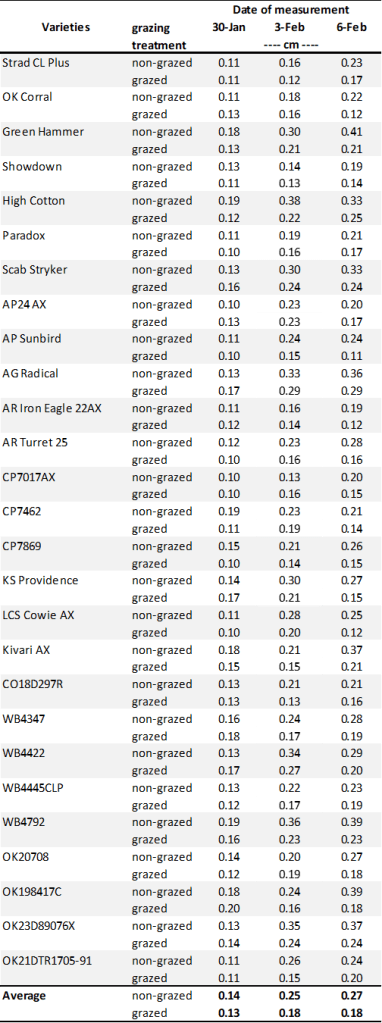

This year, we are introducing a new approach by simulating grazing with a mower in the forage trial in Stillwater. This will allow us to compare whether varieties reach FHS at different times when grazed versus non-grazed. We hypothesize that the simulated grazing treatment will likely delay FHS relative to the non-grazed treatment, with FHS differences among varieties becoming less pronounced. We also hypothesize that the amount of delay will vary among varieties, such that an early-FHS variety in the non-grazed environment may appear more intermediate in its FHS arrival with canopy removal. This comparison will provide insight into how canopy removal from grazing impacts the timing of reproductive development.

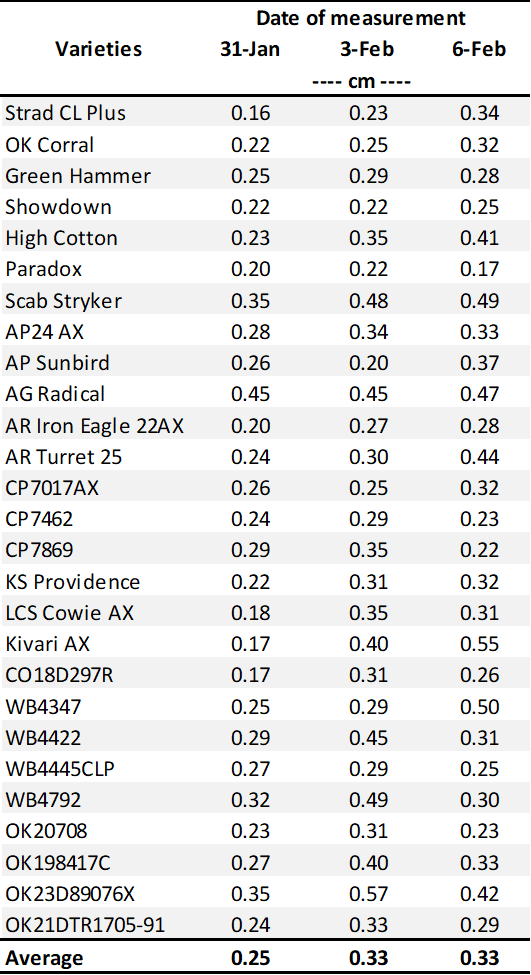

The latest FHS results for each variety planted in our forage trials at Stillwater and Chickasha are summarized below (Tables 1 and 2). Most varieties are still well below the 1.5 cm FHS threshold. However, if moisture and warmer conditions develop in the coming weeks, values could increase quickly.

Table 1. First Hollow Stem (FHS) results for each wheat variety collected at Stillwater. Plots were planted on 10/11/24, with one section left unclipped and the other clipped to simulate grazing. The FHS threshold is 1.5 cm (5/8″ or approximately the diameter of a dime). Reported values represent the average of ten measurements per variety. Varieties that exceed the threshold are highlighted in red. For the simulated grazing, plots were mowed on January 3rd, 15th, and 28th at a 2.5-3” cutting height, with the frequency representing a light grazing treatment.

Table 2. First Hollow Stem (FHS) results for each wheat variety collected at Chickasha. Plots were planted on 10/02/24, with all sections left unclipped (i.e., not grazed). The FHS threshold is 1.5 cm (5/8″ or approximately the diameter of a dime). Reported values represent the average of ten measurements per variety. Varieties that exceed the threshold are highlighted in red.

Contact your local Extension office and us if you have questions.

Acknowledgements:

Tyler Lynch, Senior Agriculturalist

Israel Molina Cyrineu, PhD student

Gilmar Machado, Visiting Scholar

Rafael Moreira, Undergraduate Visiting Scholar